Pride Over Prejudice

Offensive team names and mascots should have no place in American sports.

PHOTO | TNS

Washington Redskins running back Adrian Peterson (26) runs the ball for a first down against the Tampa Bay Buccaneers on November 11, 2018, at Raymond James Stadium in Tampa, Fla. (Monica Herndon/Tampa Bay Times/TNS)

Mascots should never demonize or give into stereotypes in the name of ‘team spirit.’ People are not mascots.

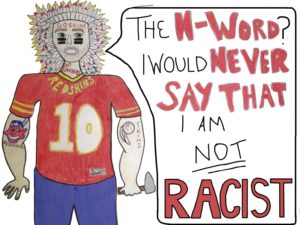

The Washington Redskins are a part of the problem. The word ‘redskin’ is a derogatory phrase that dates back to 1769. As it became more widespread in the era of Westward Expansion, it was used as a means to dehumanize Native Americans, according to the Washington Post. In fact, dictionary.com and the Merriam-Webster Dictionary define the word as “offensive,” and it is commonly listed as a racial slur. On top of this, the team’s old mascot, though it has been recently changed to a much less cartoonish (but still offensive) image of a Native American, illustrates an image of a completely stereotypical interpretation of a Native American: bright red skin, a feather in his hair and overdrawn eyes and lips, similar to images of ‘blackface’ with exaggerated facial features.

But the Redskins are not alone in this controversy. Our own Kansas City Chiefs, though they did change their old, offensive mascot to the letters “KC” inside of an arrowhead, still use Native American imagery in the name of their stadium, Arrowhead Stadium, and in their new logo.

So why are these teams still allowed to be nationally recognized and commercialized? One statistic, along with the argument of ‘tradition,’ seems to have long-time fans of these teams convinced that they are on the right side of history.

The famed statistic, coming from a Washington Post poll of 504 Native Americans across the country, concluded that a whopping nine out of 10 Native Americans do not take offense to these team names, logos or mascots. But there’s more to the story than one statistic that conveys the opinion of not even a fraction of the Native community in America (.00001% of the total Native population, actually). If this is really what is considered an accurate representation of Native American people, it just shows how much has been taken and stripped away from them to the point where even their imagery is being taken.

Organizations against these logos, mascots and team names have arisen in Native American communities. The National Congress of American Indians has organized hundreds of protests across the country and have even taken the issue up with the Supreme Court to get these names appealed. Much of the appeals are based on Dr. Michael A. Friedman’s studies, which proves that offensive mascots, team names and logos have significantly negative effects on Native Americans, especially adolescents.

While the creators of these logos continue to make millions off the use of Native American imagery, little to none of that money is put to use to help suffering Native American communities. Native Americans are the most likely people to experience violence at the hands of another race, according to the Department of Justice. Forty-four percent of Native Americans live in poverty, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. Native women are three and a half times more likely to be sexually assaulted or raped, according to the Huffington Post. Only 51 percent of Native American teenagers will graduate from high school this year, according to the Huffington Post. Native American communities are suffering and instead of receiving aid, they are being ridiculed.

Jenna Barackman

Jenna Barackman

A portion, if not most, of the money made from exploiting Native American traditions, must be used to help Native communities. These cartoonish images, branded as ‘honoring’ Native culture, cannot be allowed to fly on flags and be on T-shirts while the people depicted are suffering.

In addition to this, fans often think that dressing in traditional headdresses and in other items exclusive to Native American culture is in the name of football or baseball is okay, or, in some cases, respectable, because it is the mascot of their team. In actuality, these depictions are offensive to many natives who have fought against this cultural appropriation. These mascots give cultural appropriation validation it does not deserve.

The Chicago Blackhawks are an example of using Native American imagery but also giving back to the culture in which they took it from. The Blackhawks funded the restoration of a 48-foot-tall statue titled “The Eternal Indian”, which is a significant part of Native Americans’ cultural identity in that geographic area, according to NewsMaven. They frequently donate hundreds of thousands of dollars to American Indian Center and the Trickster Art Gallery, a gallery which specializes in the showcasing the history and culture of Native Americans, according to the NHL. Through their use of the Native American war hero “Blackhawk” in their logo is still not just, their adamant help to Native American communities does make them appear more respectable since they give back.

Native Americans are not our Sunday Night Football entertainment. They are not mascots to poke fun at and are certainly not costumes. They are not a marketing ploy or a brand. They are people, and we need to stop pretending to ‘honor’ them by using their imagery. If we truly want to honor them, action will be taken to make sure that Native communities get the help they need.